Beauty, power, and the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders

A millennial feminist and her beauty-obsessed daughter watch the Netflix show

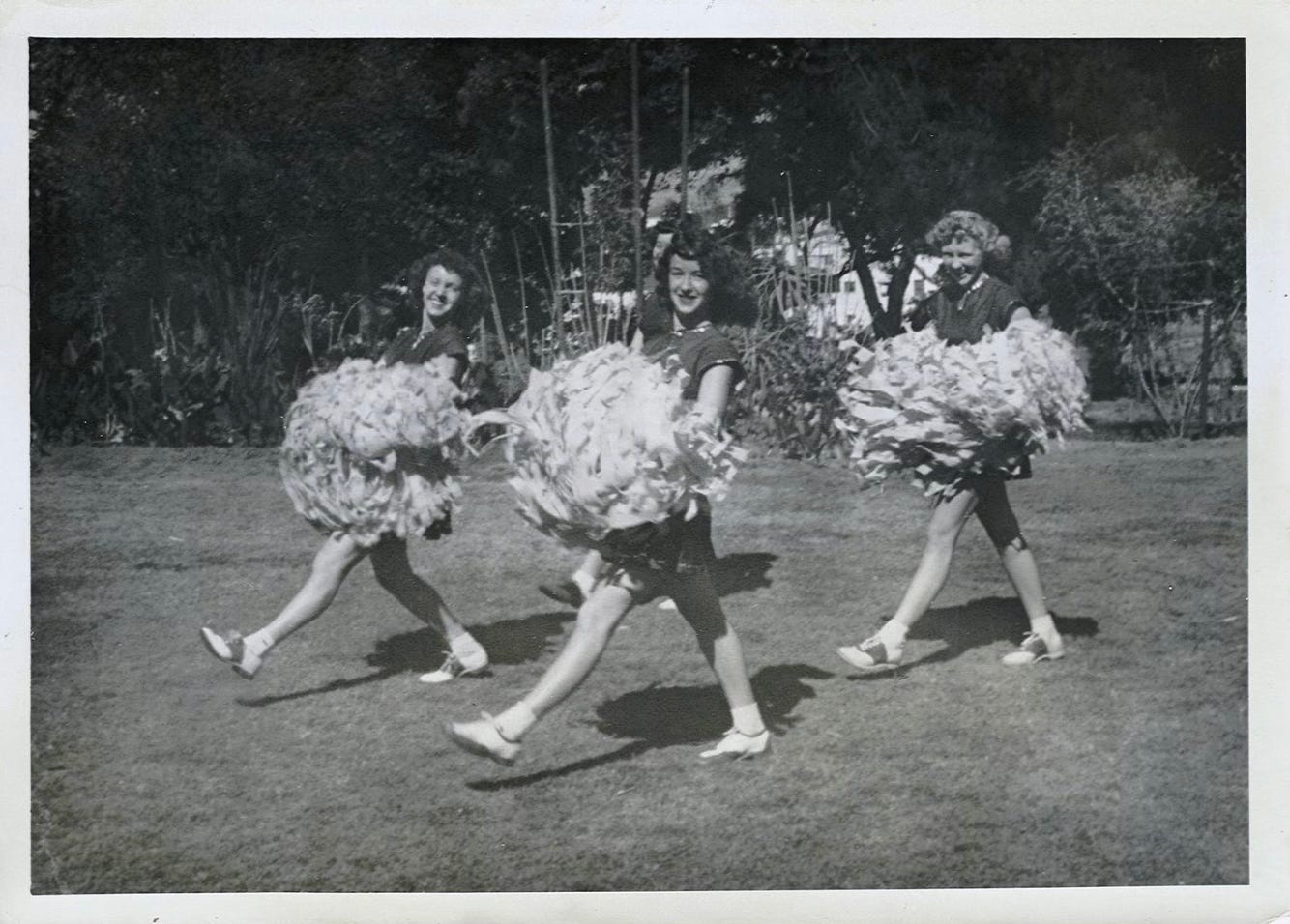

Lately I have been watching the Netflix series “America’s Sweethearts,” about the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, with my eleven-year-old daughter. The show is a can’t-look-away hybrid of reality TV and documentary film. I consented to it out of simmering guilt because I will not, under any circumstances, let my kid do “cheer.” I am too much of an obnoxious urban liberal who listens to alarming NYT Magazine podcasts about the head injury rates and corporate monopoly, and who breaks into hives at the thought of ever fastening a massive bow to a ponytail.

But my child, who is perceptive and lives in the present-day United States of America, has absorbed the ubiquitous culture of cheer and become obsessed with it. I thought this would be a nice compromise. A little cultural experience for us both.

Instead, I discovered a veritable geyser of red-hot questions about female agency, power, complicity, and responsibility. What, the show asks – in its sumptuous close-ups of these gorgeous, heavily makeup-ed women; these women whose entire lives are devoted to performing (for almost zero dollars) for men; these women who are so good at what they do and whose work is incredibly skilled and physical and challenging in its own right, and also based almost entirely on their appearance – makes a woman powerful? Is it her looks? Is it the money she makes? Is it her talent? Is it her ambition? Is it her intellect? Is it her “success,” and if so, as recognized by whom, and measured by what?

Is it feminist to abhor the cheerleaders for their docile “Yes ma’ams” and their meticulous attention to their waistlines and their adherence to virtually every toxic female norm ever perpetuated? Or is it feminist to respect their choice to do what they love, to shed sweat and blood and tears for it, even if it is a highly traditional choice in line with expectations, a choice that seems to set a bar for “femininity” that many women cannot and do not ever want to reach? Can it be both?

What I do know is that within the course of several episodes I was banned from watching the show by my preteen daughter. Our cuddly cultural experience had devolved into a long series of tirades in which I paused the iPad and said, “Okay, Elena, you have to understand that this is diet culture, and it’s so oppressive, and it leads to…” or “Okay, Elena, this is INSANE because football players make millions of dollars but they…” until Elena – this bold and fearless feminist I have raised! – shouted, “YOU ARE BANNED FROM EVER WATCHING DALLAS COWBOYS CHEERLEADERS WITH ME AGAIN!”

There are several things that you, dear reader, need to understand here. One is that Elena, as mentioned above, is a preteen girl, so boys, sex, attraction, beauty, etc, have all recently come online for her in a major, hormone-addled way. Another is that she is an athlete: a swimmer who has swum hard four nights a week for the past five years, and who delights in physical challenges and has always been interested in the body. And the last is that she is fascinated by beauty.

This is one of those fascinations that I can see going way back. When she was three, she had a preschool teacher who looked a lot like a Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader (Preschool Edition). This teacher wore pencil skirts and neatly pressed button-downs, not butt shorts and cowboy boots, but her beauty was that kind of classic, girl-next-door, French manicure-and-perfect-white-smile type.

Elena was obsessed with her. When the class did some sort of Dr. Suess-inspired project in which they had to choose something they wanted 100 of, Elena chose “100 long nails like Mrs. S.” (Keep in mind that I have gotten a manicure exactly once in my life, for my sister’s wedding, so Elena’s fascination was NOT coming from the home front.) Some time that year a person who did not have children made the tragic beginner’s mistake of asking Elena if she thought I was beautiful (perhaps assuming children have the built-in politeness of adults; spoiler alert, they do not) and Elena shrugged and said, “Not like Mrs. S.” Of course she was right. No way in hell I was beautiful like Mrs. S. Someone one asked me to describe my aesthetic and I said, “Camping?” Mrs. S curled her hair and did a full face of makeup every morning.

It is important to note here that Elena is beautiful. Noting this makes me uncomfortable. It feels inappropriate. It feels gross. It feels like being the waiter in Mexico – there is one, every time – who asks in a voice like one you might use with a teensy dog, “Y que quiere la princesita preciosa?” And what does the precious little princess want? Ick, heeby-jeebies. But why does that feel so gross? Is it because I have such a knee-jerk reaction to beauty, a kind of violent ethical resistance to it as an aspirational good, something to admire and strive for? Because I hold strong to the righteous notion that focusing on it signifies vapidity?

But beauty is also part of who my child is. She is a choose-your-ethnicity child. In Sweden, the Filipina and Vietnamese ladies at the naked bathhouse told her she was so beautiful, she had to be Asian. She could be, with her skin that darkens almost to coffee when she tans and lightens to a pale gingerbread in winter. She could be from anywhere in North or South America. She is a true mix of my European mutt blood and Jorge’s indigenous, Zapotec ancestors.

She knows she is beautiful. This also feels very weird to write. A secret we’re not supposed to admit. Something we’re not supposed to see or acknowledge if we’re educated the right way. But she does know it, because how could a kid with any remote sensitivity to body language and human interaction and social norms and the cultural ether not know it? And especially a kid who is so social, like mine, and especially one who regularly goes to Mexico, where it is still 100% socially acceptable to say things like, “You’re gorgeous! You’re fat! What happened to your hair?”

So she knows. But she isn’t sure yet what to do with that knowledge. It’s something she’s holding. Figuring out. And you see, I never had to figure this out. I was a cute kid, nearly white-blonde with bright blue eyes, always sporty and tan, but prone to wearing the same sweatshirt with a picture of a coonhound and the caption COONHOUND. In college, I had a friend who was truly beautiful, who later went on to become an actress in Paris (hi, beautiful friend!). One time in Madison when we were out for a walk, a guy approached and told us he was a talent scout. He said to her, “You are absolutely gorgeous.” And then, realizing I was there and likely someone whose opinion would carry weight in whether or not she would give her number to this random dude on the street, he improvised: “And you have a really cute freckled thing going on.”

I have absorbed many of these kinds of remarks. At my grandpa’s funeral, a cousin (remember friends, kids will say the quiet part out loud!) introduced me and my sister by saying, “Mary’s the pretty one, and Sarah’s the smart one.” This was devastating for my sister and me both, a testimony to the power of kids to really crush it observationally. Of course, I internalized this narrative. I had no illusions (okay, maybe I had some illusions?) of being stunningly beautiful, but I decided that it was superior to be smart and that beauty was superfluous and dumb, and in this I found commiseration in feminism.

Why would I want to aim for being attractive to men when instead I could absolutely slay at a graduate seminar in philosophy of science? (To me, this was an obvious question). My friend Rachel and I used to mock the “one-string” sorority girls who wore halter tops suspended by a single string in zero-degree Wisconsin winters, and prided ourselves on being able to beat boys at racquetball and sustain a stimulating intellectual conversation after 47 Bud Lights.

Later, in Oaxaca, after I’d met Jorge, I raged about the Mexican male artists who treated women as if they were simply beautiful objects to be photographed: “las musas,” I called them, existing only to pose in exquisite costumes on the arms of their decorated males, discarded when they aged out.

It is clear that the woman who relies on her beauty for her power is playing a game she will lose. She knows this, she has to know this, but perhaps the rush of power smothers that denial. I have known women who suddenly find themselves replaced by younger models just as they replaced the aging woman before them, each one confident that their story would be different – that somehow, their hair wouldn’t thin, their skin wouldn’t wrinkle, their man would lose his appetite for the wide-eyed ingenue. Some of these women have spiraled into despair. What is left to them? What is theirs? Their power is entirely conditional. At a certain point, clinging to it becomes tragic.

One Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders episode focuses on an alumni reunion. The women, most of them at least fifty or older, still have full faces of makeup and Barbie hair and knee-high white boots, along with the subtle and not-so-subtle markers of plastic surgery. The identity that fits the young women so seamlessly reveals itself a decade later as a costume. One shot zooms in on the back of a woman’s knees, where panty hose have bunched up at the top of the ubiquitous cowboy boots. It’s a funny shot, a cruel shot, a brief two-second glimpse of the stakes: the misogyny that craves beauty waiting with contempt when it collapses.

But other sources of power change, too. Everything, as the maddening Buddhist maxim goes, changes. Careers change, talents change, personalities change. Beauty is only the most obvious, outward example of this change – it would be a mistake to assume that what’s “deeper,” beneath the surface, is that much more solid and permanent. How many of us feel and think mostly the same ways we did twenty years ago? Perhaps because beauty is a quality mostly associated with women, it comes in for more ridicule; a once-beautiful woman whose power may have been resented, feared, or judged finally fades from glory and her haters rub their hands in delight. But really all of us are only clinging to temporary forms of power, illusions not so different from the high slash of a cheekbone, the perfect circle of a hip.

“It’s what’s inside that counts!” I tell my daughter, but just like she reads the subtlest signals of race and class, she knows this isn’t entirely true. It’s a quaint adult aspiration, just like the golden rule. We all notice beauty, and we’re all influenced by it to some degree, no matter our beliefs about its nature and importance. I warn my daughter not to associate it with virtue; if anything, I preach, the pretty boys are the most dangerous. Do not be fooled by appearances. Do not let yourself be charmed out of your dignity and your depth.

And by the same token, I tell her, do not ever believe you’re superior to anyone else because you look good. Do not believe that being thin or having voluptuous hair gives you the right to lord yourself above anyone, bestows on you any immediate worth. You are no better than the girl in the Coonhound sweatshirt and the hideous, inch-long, smiling Dalmatian earrings (aka, 6th grade me).

We’ve had these conversations so frequently that Elena once remarked, “Mom, do you WANT me to be ugly?! Jeez!” And the remark made me wonder. Of course, I don’t. Right? But like all children who have some quality or talent their parents never possessed and don’t understand, I am mystified and a little scared by beauty. I don’t want her to form her identity around this fragile, and frankly, superficial thing. I disdain it. And yet inevitably, she will. Because she can’t avoid it any more than she can avoid the fact that she is Latina or a woman.

And I wonder, too, if I am so wary of beauty in part because I haven’t figured out how to integrate it into a more complete model of feminism. Because I still believe that it’s better, more laudable, morally upstanding to not care about that: to be funny, brilliant, critical, wise, anything but beautiful.

Beauty, as I imagine it, is unearned. It is weak. It is fake. It is temporary. It is surface. All of these things are to a certain extent true. But what is also true is that as a woman, I resent having to be beautiful. I resent the assumption that this is my duty, that this is ultimately how I will be measured. I resent having to play what I see as a dumb, trivial role: the pursed lips, the hair flip, the caked mask over my actual face. I resent my worth being calculated by the length of my eyelashes or the size of my belly. I don’t want to play the game. I hate that the game exists. But I also wonder if it’s possible to value beauty through a feminist lens: to see it not as a threat or a maxim for all women, but as simply one more possibility. An expression of creativity, even fierceness.

Of course, beauty is inextricably intertwined with patriarchy: women starving themselves to reach a certain size, injecting poison into their faces, lightening their skin and hair with bleach and toxins. Women trying to look exactly the same – like a Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader, who always has a teensy waist, a pound of makeup, and shiny, bouncing $500 hair. I want Elena to know it doesn’t have to be that way.

But I suppose I also want her to know that if she ever does desire to be a Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader, there is a different (feminist?) way to go about it. That if she ever wants to be beautiful for a living, she must demand her worth. The irony is that even the most mainstream, classic American culture (football!), which fetishizes female beauty, doesn’t actually value it at all by that most American of metrics: dollars.

The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders earn about $15 an hour. Many have three or four jobs to sustain themselves. Of course, the Dallas Cowboys football players are multimillionaires! But “the girls” do it for fun! Because it’s a privilege! Because they like it! As if they simply stood on the field and smiled for a few hours.

These women spend thirty to forty hours a week on physical training alone. They put their bodies through grueling workouts to effortlessly perform their core routine, “Thunderstruck,” which as Vogue describes it, “involves both a 50-yard sprint in under eight seconds (in cowboy boots!) and chorus-line jump splits.” Most men, I dare say, would not be able to muster the stamina required to be America’s Sweetheart. The cheerleaders have to memorize dozens of dance routines and perform them with millisecond precision in a stadium of tens of thousands of screaming people.

When they come on stage, they suck up all the electricity in that stadium for six minutes. All eyes on them. Even watching on our crappy little iPad, we cannot look away. They are so good at what they do. They are little bolts of lightning that snap our eyes to their high kicks, their impossibly wide smiles, their flung-back manes slicked with the slightest drips of sweat.

This is work. But of course, because they’re women, it is not treated as such. It is an honor to perform. “I just love to dance,” shrugs one sweet cheerleader who one wants to reach through the screen and throttle. Smile and be grateful, sweetie, because there are 100 more girls where you came from. “Yes ma’am!” It is the yes ma’am that gives the show that mesmerizing train-wreck quality for the millennial feminist – are women still freaking doing this in 2025?

But it’s also what makes this season so rewarding. Finally, two women on the team advocated for a raise. I negotiated hard with Elena to be able to watch with her again: she got Cheez-its and lemonade and I promised to suppress all of my cultural, social, and political education. But I did shout for joy when one cheerleader suggested to the others over breakfast, “Maybe we should refuse to sign our contracts.” Now that is power, baby! “Be that person!” I told Elena. “Be the one who is not afraid to speak up! Be the one who knows what she’s worth and demands it! Be the one who will fight for everyone!”

“Mom,” Elena said. But if beauty is a choice, so is docility and submission. They don’t have to go hand in hand. If you can kick high enough that your knee touches your face, you can get paid a million dollars just like any football player, and you can damn well demand it, yes ma’am.

I have tried to hide beauty from my daughter. I do not let her go to Sephora and will not, ever, on my watch. I do not talk about people’s looks or bodies and I tell her that if anyone she meets does this – some girls at camp last summer, for example, were calling other girls fat – she needs to speak up or keep her distance. But I have also learned that one of the really fun paradoxes of parenting is that the more you try and cordon something off, mark it as a big bold NO, the more attractive that thing becomes. So I try and keep little pathways open for beauty, for bringing it out into the open and discussing it.

“Look at their hair,” my daughter coos, “and how many makeup brushes they have…” as the camera does a lusty pan over a cheerleader’s dressing table. It kills my soul a little, friends. But who am I to say, you’ll be so much happier working towards a PhD in English? You’ll be a better person without an inch of foundation?

I don’t want her to dedicate her life to pleasing a man (or a stadium full of them). I don’t want her to appease a misogynist society that doesn’t want to compensate her for her work, that sees her only as a dispensable object. I don’t want her to be superficial, empty, basic. I want her to be a complex deep person who reads books and engages in passionate debates about the origins of the universe and is not afraid of picking up worms and getting her shoes filthy! But why do I see this as diametrically opposed to the work of being beautiful?

Is it also possible that she, like some of these cheerleaders claim, simply loves the physical activity – and my daughter, a born athlete, absolutely does – and that she loves being beautiful? That she loves the softness of her own black hair with its natural sun-bleached tips as it sways across her back, that she loves her big smile brightened with coral gloss, that she loves feeling the sashay of her body and its electricity? What will she make of that? How will she navigate it? She’ll have to answer for herself.

“You’re nobody’s sweetheart,” I tell her, and she winks.

Recommendations

Hello friends!

My brilliant friend Jenny started a newsletter! It’s free and it’s sure to be beautiful. Check it out.

This book is absolutely gorgeous and I’m not exaggerating when I say it has renewed my faith in language.

I listened to this audiobook and it was a total delight. I laughed, I cried, I yelled at my family to get out of the kitchen while I was cooking so I could keep listening.

Holy cow is this depressing but necessary reading about AI and creativity and Substack and writing!

I’m about three-quarters of the way through this book, by the writer

, and it’s as lovely as promised. Her newsletter is also always full of excellent recommendations.Many of the people who voted for our current administration are mind-blowingly ignorant (and thus incredibly entitled) about where their food comes from. This story is a case in point.

The writer

had a really interesting essay this week about what both the left and the right get wrong about pronatalism.Have a lovely weekend, everyone, and please say hello below with any thoughts, reflections, and/or recommendations!

Being a man, this would be a minefield for me to step into. I do appreciate the nuance that you bring to the topic. And one of the things I like about your writing is how you continuously question yourself and your assumptions, maybe not changing your mind, but loosening your grip on your beliefs.

I will say I usually find the Dallas Cowboy cheerleader/Barbie look uninteresting. I don’t consider it beautiful, but a caricature of beauty. However, there are real people inside these white boots. Their motivations are varied, as you say.

As I grew out of adolescence and became less hormone driven I realized that what made a woman attractive to me was her intelligence, wit, curiosity, physicality, compassion, and such. These attributes in women, in anybody really, are what makes me want to spend time with them.

Finally, bringing in the Buddhist perspective is always useful. We will lose everything, so don’t hold on too tightly.

🩷