Paid subscriptions make this work possible. 💚 Become a paid subscriber today to support my writing and get access to weekly mindfulness practices, recommendations, community threads, and more.

On Monday of last week, we sent our Unsworn Declaration of Homeschooling, Vaccination Record, Health Record, and List of Educational Objectives to the Pittsburgh Public Schools Office of Homeschooling, and pulled Elena officially out of school.

Why?

The tangible answers:

We loved certain aspects of Elena’s school. The teachers were largely wonderful, dedicated humans who really cared about her. We were very drawn to the school’s philosophy of play and environmental education. We cherished the community of parents, the emphasis on creativity and science, the hiking and outdoor adventure.

But we also witnessed many disturbing behavioral issues – students threatening suicide, throwing and breaking things in the classroom, screaming, cursing, attacking other students – and no consistent, functional ways of dealing with these issues beyond a few minutes of mindful breathing, an email home, a chat in the hallway with a behavioral aide. A student who held my daughter in a headlock and tried to smash her head against a desk was told to write a letter saying sorry. I witnessed one student purposefully cut another off on a bike during a biking course, causing a major crash that luckily resulted only in scrapes and a bloody nose.

At the same time, recess and sometimes lunch (lunch!) would be withheld from students because of minor “misbehavior” like not standing in a straight line. I addressed these inconsistencies with the administration and received a short, lukewarm, “that doesn’t happen here” response, then corresponded with other parents who’d sent similar letters and been told the same over years. Elena came home crying one day because she’d been told to eat entirely in silence since she and her friends were “talking too much” during lunch.

Then there were the screens. We discovered that blocks of time – like typing class – on our daughter’s schedule were not actually teacher instruction, but “free choice” time on iPads, where students could play whatever apps they wanted, with no supervision. Elena was playing a “math app” that was essentially a super low-budget video game where every twenty minutes or so a question like “What is 2x1” would pop up to allow her to pass to the next level.

Students sometimes spent hours a day on these iPads. Screens were the default whenever a teacher was absent: in Spanish, for weeks, the entire class consisted of playing an app in which students raced one another to guess a vocabulary word. Half days of school were devoted almost entirely to watching movies.

Most difficult and contentious was the question of race. Elena is Latina. She reads as Latina. This is something I have had to learn. As she is mixed race, I thought for a long time, well, she could be interpreted either way, as white or Latina. But I’ve learned through many lived experiences – and difficult conversations with Jorge – that this is not the case.

Jorge and I were highly aware of the fact that educational outcomes at this school, and most public schools, are starkly divided along racial lines. We were also aware of the substantial research showing that teacher expectations are the single biggest factor in student success, and that teacher expectations – especially the expectations of white teachers – tend to be lower for students of color.

This has been our experience. I found myself consistently having to push for Elena to be given access to “enrichment,” even when her test scores are high. I can see how, over the course of years, these expectations wear on students. Elena started at this school in 2020. It was closed for nearly a year and a half, and provided almost nothing in the way of instruction (20 minutes per day of virtual math/literacy). Elena had done well in math in kindergarten (though who knows what kind of indicator that is!), but when she started back in school at the end of first grade, she was, like most American children at that time, behind.

Meanwhile, since she read nonstop on her own, she was advanced in literacy. Over time, she has gotten more advanced in literacy, moving into the top percentiles in tests, but she’s progressed in math only to proficiency. She is not allowed into enrichment groups in either subject.

I have been told over and over “she’s almost ready for enrichment” but somehow, she never gets it – and never advances in math. I don’t necessarily blame the teachers – they see a student who has gotten X score and come into X math group, and they identify her as such. They have twenty-five kids, many of whom are really struggling with behavioral issues, and so one kid who is at grade level without any issues isn’t going to get a ton of attention. But it is interesting that ALL of her white friends are in enrichment, and she and her one friend of color (who is also the only other bilingual child in this group) are not.

We had an intense experience with her second grade teacher in which, after going five years in another school without a single complaint from teachers (other than her talking too much 😅) we received three emails home in the second week of the year. They were all strongly worded, warning us that Elena was violating the school’s behavioral code. The first was because she tickled another child in the lunch line. The second was because she talked about “boyfriends” during recess. And the third was because she talked again about boyfriends during recess (😭 pray for us during adolescence). Meanwhile, other students were getting in fist fights, breaking things, screaming obscenities at the teacher.

I asked for a Zoom meeting because I was concerned. I met with the teacher and told her we’d never had any behavioral issues before. She was understanding, and it was all suddenly no big deal. She also saw me: a white, middle-class mom, asking questions. We never received another email home. Eerie, disconcerting, the experience stuck with me.

I have had meetings with the school in which I’ve pointed out that Elena is very socially motivated and, seeing as all of her white friends from our neighborhood are in enrichment, she would love to be there as well and would thrive especially with that competition and impetus. I’ve also pointed out that NOT being allowed access to this sends a powerful message to a student like Elena – and to her friend, again the only student in her cohort from our neighborhood not to get access to this enhanced curricula. They watch as all of their friends leave the room and they stay behind. But no dice. No enrichment.

Of course, we are not rearranging our entire lives because we want her to have better math scores! The point is that when teacher expectations can have such a huge impact on student outcomes, I fear that she is getting and doing the bare minimum, and that over years, she will learn that she is only capable of X, and believe a story about where her capacities lie, and that story will become powerful and incredibly difficult to break. I see it in my friends. In my students.

There is this progressive notion that public schools are inherently noble and we should all be doing advocacy work to improve them. But I have seen parents launching organized campaigns to get iPads out of classrooms, spending entire academic years in meetings fighting to get Lucy Calkins’ curriculum out of the school, and – nothing. No change. When I asked for Elena to get more access to enrichment at school, I was told by an administrator, “Oh yes, we talk about that all the time!” “Great!” I said. “And what are you doing?”

It is also interesting to me how so much of the discourse about public schools relies on parenting assumptions that in any other context would look retrograde. “It’s good for them to witness adversity,” friends will tell me, when a child sees another child punched in the face in the bathroom, or “They have to learn responsibility,” when a teacher takes away recess because one child refused to do a worksheet. I doubt any of these parents would applaud their children witnessing a domestic screaming battle, for example, or would lock them in their room because they were rude to a sibling.

It’s also hard to imagine, especially with the discourse nowadays about leaving toxic work environments and self care and boundaries and integrity, any adult insisting that another adult should remain in a workplace that consistently makes them sad, bored, angry, scared, or intimidated, with colleagues who may be outright aggressive. But forcing children to experience this in school is seen as some sort of collective good: a badge of honor, a rite of passage.

So many of us are listening to the podcasts and following the Instagram accounts and reading the books about the significance of rest and the devastation of late stage capitalism and the damage of productivity culture and the psychological, environmental, political, and social fallout of a society based largely on consumption, status, abstract knowledge, cognitive prowess, achievement, and wealth. But whereas we talk often about work, we don’t talk nearly as much about school.

Why, at 5 and 8 and 10, are kids asked to put in an eight-hour workday at institutions they most often did not choose and do not have any power within, told exactly when to eat and go to the bathroom and sit and stand and move and talk, given almost zero control over what and how they learn? How does this produce a liberated citizen? Someone passionate, independent, critical, insightful enough to confront the massive problems this generation will face?

I’m sure plenty of people can come up with brilliant answers to these questions, and I would love to hear them. I know school works for many families, and for a while, it also worked for us, and maybe we will return to it at some point. I know there are all sorts of compelling arguments for school, and many people rely on and love their schools. I pose these questions to challenge some of what we take for granted about schools, since homeschooling is seen as such a radical or extreme position.

The larger answer to our personal “Why?” is not about academic outcomes or test scores or expectations or school environment. It’s not negative, but positive: to remake our family life.

I remember walking the dog one day during COVID and thinking, out of the blue, wow, none of that mattered. I wrote a book. It received a great review from The New York Times. It was on a billboard in Times Square. It was everything I’d dreamed of in grad school.

But so what? I’m glad I did that work. I want to do more of that kind of work as a writer: work that shifts our existing paradigms, ignites and moves people. But really, it didn’t matter that much. Not nearly as much as I thought it did.

I remembered my grandma in hospice. The night I stayed on my own, holding a chocolate milkshake to her lips, watching her sip carefully as she moved with grace and openness into the process of dying. “You’re a good kid,” she told me. This had nothing to do with my books. With The New York Times.

At the heart of our decision is the intention to live the questions we have been asking now for years: How does one live a wise, meaningful life? How do we break free of these systems that we feel are increasingly dysfunctional and out of tune with the very real problems – and potential solutions – in the world? How do we get off this treadmill where it seems like all of us are on autopilot, eating in the car, yelling at each other to hurry up in the shower, doing – what exactly? Working on something always for the future, for some time when we’ll have time.

Instead, maybe we could wake up and spend two hours reading Stuart Little. Or watching birds. Maybe we can eat roasted sweet potatoes outside at midday. Of course, it’s not all luxury and indulgence and lounging with scented candles; I have to work, Jorge has to work, Elena does actually have to learn something. But we can set our own rhythms. Human rhythms.

We can see each other. Be with each other. We can ask the question of what really matters, challenging the culture of status, achievement, and “success” in which I’ve long immersed myself. I can ask myself what work I really need to do, and make and demand the time to do it – and let the rest go, because one day I too will have my last chocolate milkshake, and what will matter?

That is the measure of the days.

I want to address the question here of privilege. Maybe there is an assumption that you have to be wealthy and in some extremely cushy situation to homeschool. I don’t believe that’s true. We are two artists, living in a small house on a small budget in Pittsburgh. The hardest thing for us is managing two careers and doing homeschool at the same time, which we’re doing right now by a) waking up at 5 am and working until 8 am (me) b) working every day while Elena is at sports/activities from 3-8 pm (she does running and then swimming because she needs an insane level of exercise to be a happy human being) c) trading off teaching certain subjects (Spanish, him; writing, me) and working while the other is teaching.

This may not prove to be sustainable. We’ll see. But I lay this out to say that we are not independently wealthy and neither of us is drawing some fat tech salary nor has a trust fund nor some sort of hidden fount of passive income (if only!), and there is some financial stress in giving up the certainty and stability of time. BUT – for us, it is worth it, for what we will gain in meaning and relationship.

Can everyone do this? No. Does that mean no one should do it? Does that mean that only wealthy/obnoxious/privileged people do it? As a tiny tiny sample size, the families we know and love who homeschool are NOT, by any means, wealthy. In fact, they tend to be families who are already somewhat unconventional and earning less than most people we know. A scientist dad and a stay-at-home mom who homeschool their four children in Mandarin and English, growing a big garden of goji berries and sweet potatoes and inviting our daughter over for hot pot. A pair of artists with three kids. A former preschool teacher and a carpenter.

These are not people who’ve sold a widget for 8 million dollars and are now Instagramming their children weaving hand-dyed wool, okay. All of this to say: don’t dismiss it on this front.

When Elena woke up that first morning at home and we didn’t have to rush to shove oatmeal in her and hurry her to the bus stop, it felt crazy. Radical. Bizarre. Like the world had ended. We are free, I thought. We can go to Mexico tomorrow if we want. We can drive to West Virginia and camp at the free campground. We can read for six hours, or build a fort in the woods. This is what gives the bigwig institutions the jitters.

In an article about homeschooling that presumed the quality of schools solely from their test scores (beautifully and unintentionally illustrating the why of many homeschoolers), The Washington Post declared with great solemnity, “Many of America’s new home-schooled children have entered a world where no government official will ever check on what, or how well, they are being taught.”

How bizarre to frame this notion as a sort of pearl-clutching horror scenario when our government is currently using our taxpayer dollars to send overseas massive bombs that will be dropped on children. When our country has the highest rates of child poverty in the world. When our government routinely fails to protect migrant children and turns a blind eye as they work in our slaughterhouses and factories.

When, in fact, schools where government officials are supposedly checking on what and how well students learn have generated a situation in which, (if we are to return to test scores as our metric) according to the National Assessment of Education Progress, fewer than forty percent of eighth graders are proficient at reading.

In a society so relentlessly focused on the rational, measurable and quantifiable, when the numbers of test scores alone earn schools the label “excellent,” one of the challenges of opting out is coming up with language to describe what is unquantifiable, indefinable, immeasurable.

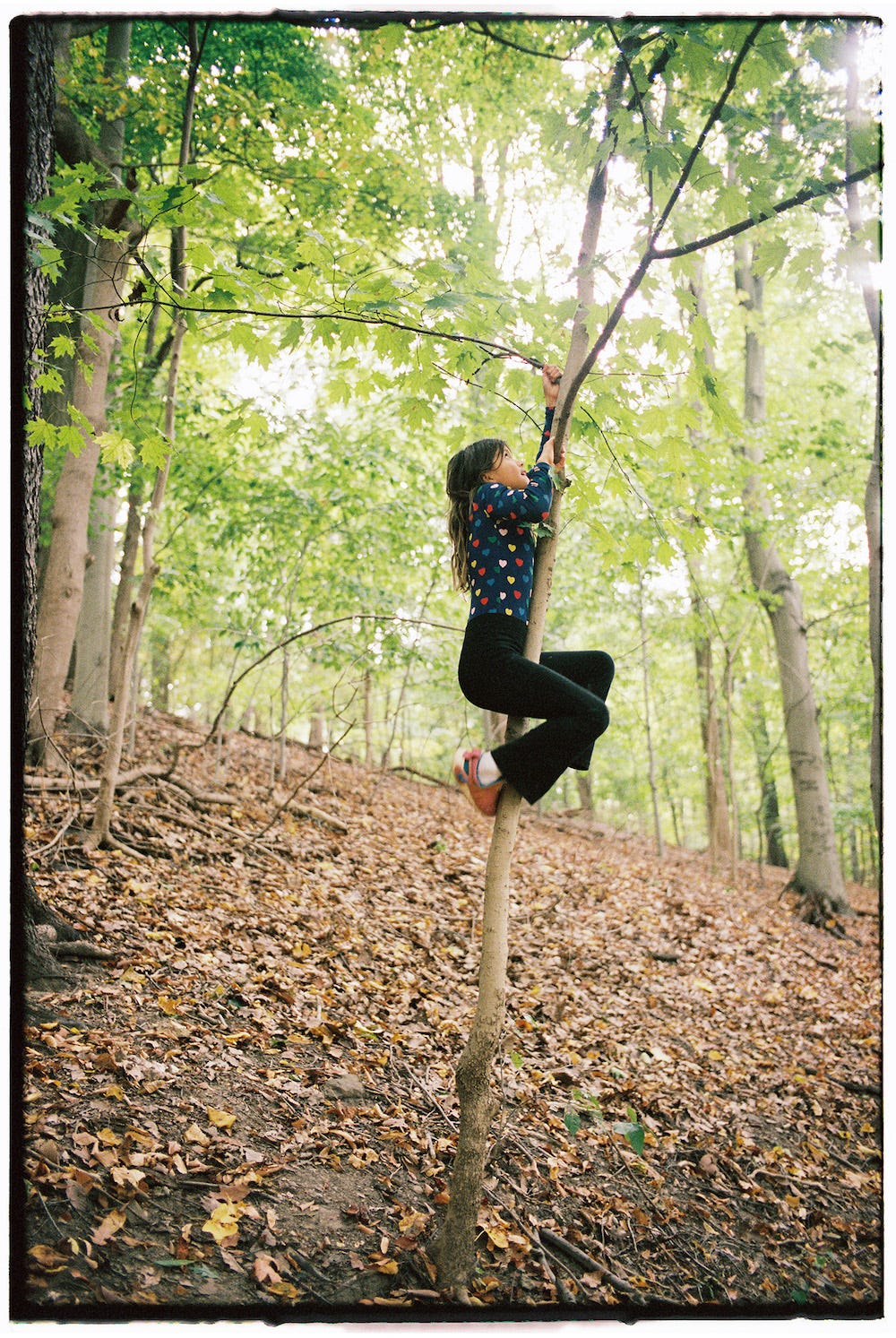

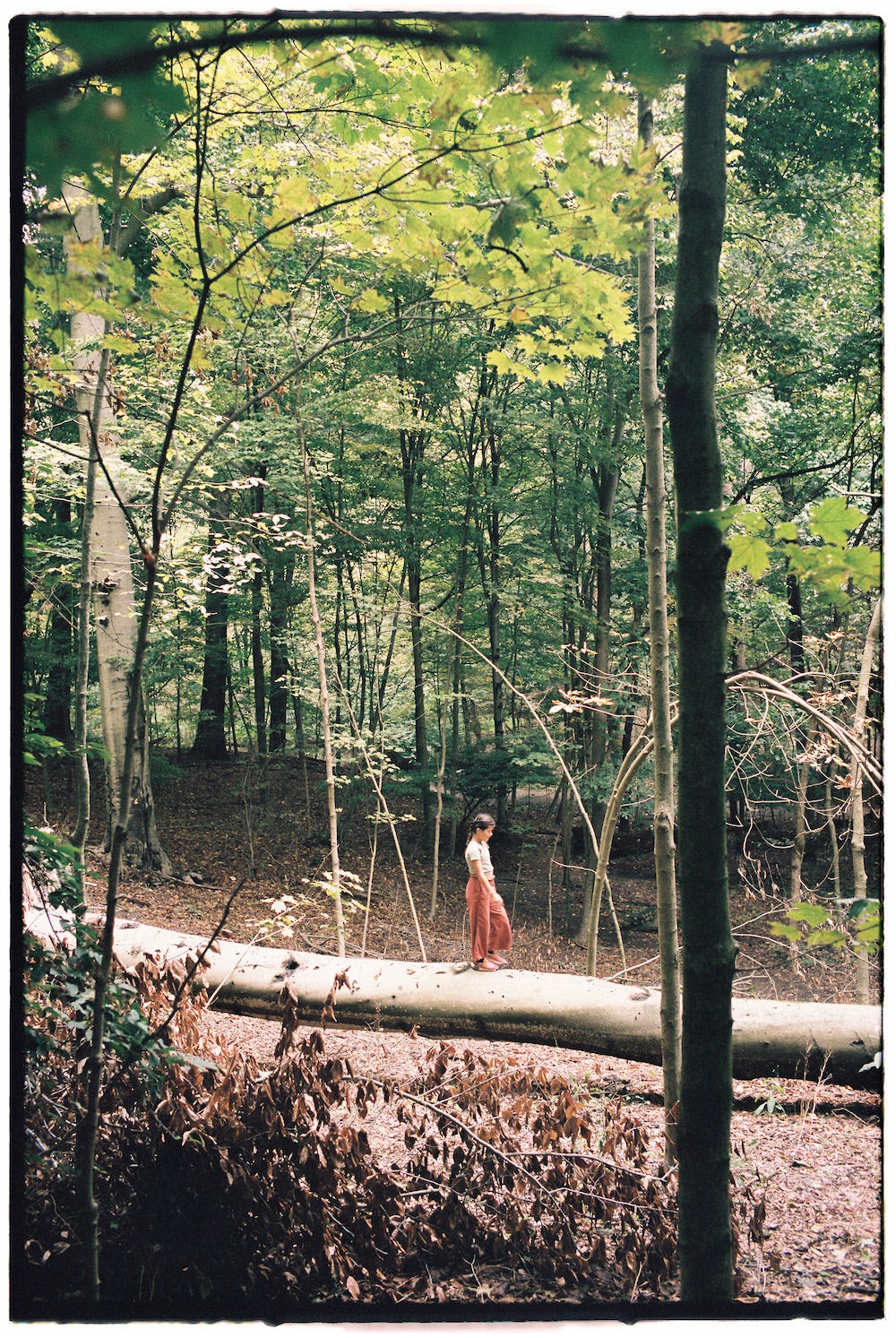

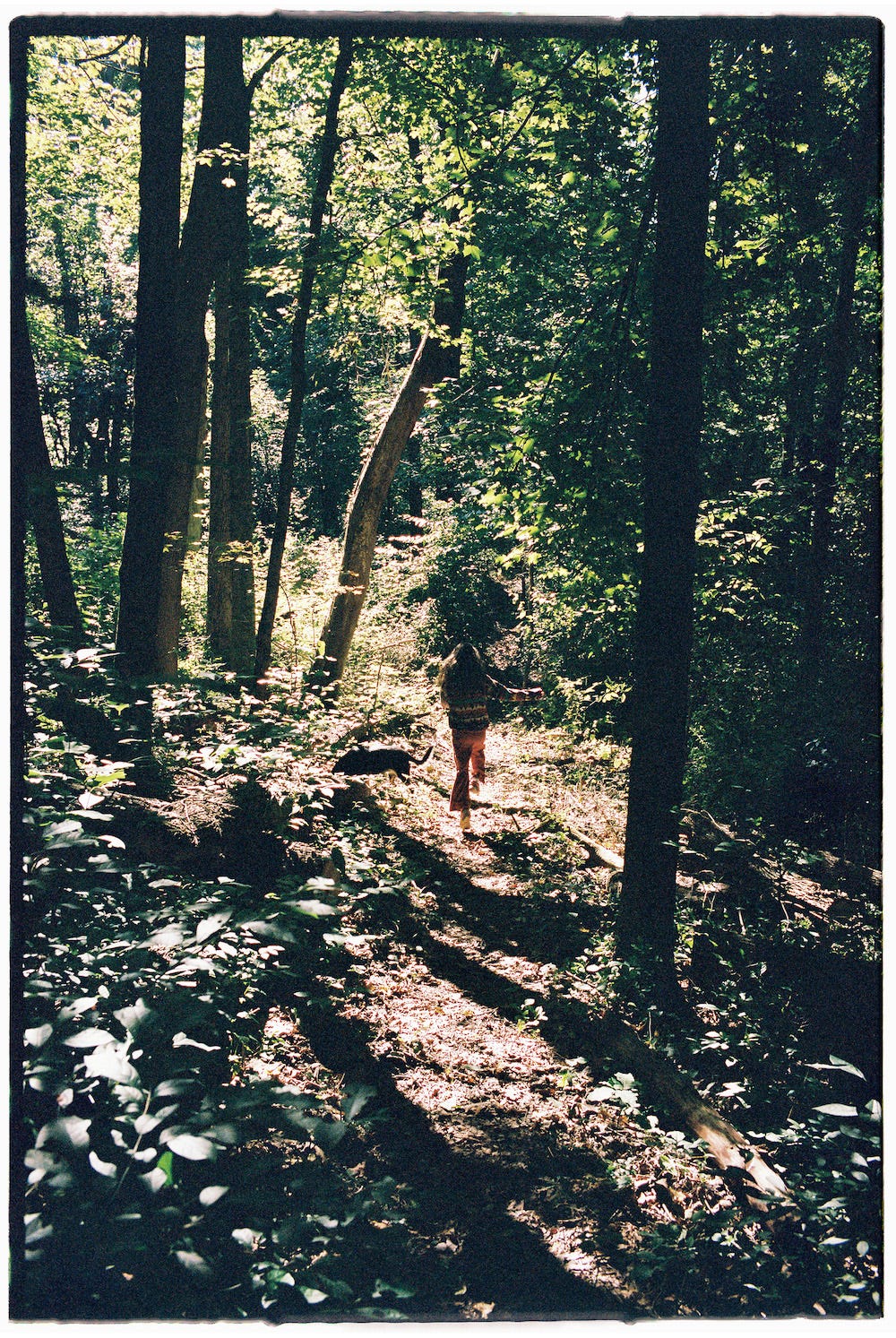

But maybe: long hikes in the park; substantial, meaningful lunches together; working side by side at the kitchen table; taking care of animals; getting deeply into projects; witnessing our child’s growth and passions and struggles; knowing her profoundly, and knowing each other, and encouraging her to know herself; building a family culture centered around the natural world, curiosity, love, and connection; honing the skills of listening, honoring, acknowledging and respecting one another. Feeling deeply into our needs, finding the edges where we can push ourselves. Connecting in new ways with our neighbors and our place; being creative and proactive in seeking community-building beyond school.

And dreaming. Of new ways of being and possibilities for our own lives, but also for the society we live in: it doesn’t have to be the way it’s always been. The systems we have now are just one choice. Just one possibility.

We can create new ones. We can draw inspiration from childhood, where everything is subject to question – Why? Why? Why? – and where envisioning radical alternatives is joyful, playful.

Elena was the one, above all, asking to homeschool. Had she wanted to stay at school, we happily would have complied! After all, it is infinitely easier. But ever since Covid she has requested, sometimes with desperation and sadness, sometimes with mere curiosity, to stay home. We have said no. Maybe later. It seemed impossible. It still seems impossible on many levels.

But after years, we have come to realize that like many children, Elena is seeing clearly what we are feeling: that these systems aren’t working any longer. That we could maybe, if we chose to, give them up. That it might be scary and difficult and complicated but it’s possible.

Dream; leap.

One understanding I’ve come to recently is that many of the people who make our world – the ones with money, the ones with power, the ones shaping our daily realities – are not dreamers. Many of them have limited imagination. They are not bad people, necessarily – many are kind and well-intentioned.

But they are the people who have risen to the top in a system that privileges left-brained, pragmatic thinking above feeling, being, experiencing, somatic awareness, art, beauty, and spirituality; that associates prestige and value with degrees, institutions, corporations, and the endless production and accumulation of “knowledge,” no matter how thankless or draining; that rewards fealty and conformity to said institutions and corporations above personal and collective liberation and independence; that has no language or reverence for the sanctity of childhood, community, the natural world; that suspects, penalizes, and pathologizes that which cannot be measured, explained, quantified, and pinned down.

We talk so often to children about dreams. But the adults in charge largely don’t dream. They plan, study, assess, execute. Not bad skills, in and of themselves. But what of the dreaming? What of the capacity and the deep desire to imagine a world radically different from this one, where war isn’t the default, where we aren’t actually obligated to take as much from the earth as possible to make as much money as we can before the next human does, where we understand that we share 65% of our DNA with chickens and 24% with grapes and the idea that we are one is as much literal as it is poetic?

Dreaming leads to risk. Dream long enough, hard enough, you might do something crazy. Something that breaks from existing reality.

Last week was hard; I’m not gonna lie. But if there is one thing I have learned thus far in this life it’s that the most difficult efforts are always the most worthwhile, and also the ones you’ll most regret not making down the line.

Having a newborn is hard. Doing a 45-minute body scan meditation every day is hard. Leaving a lover is hard. Moving to a new country is hard. Starting over after an artistic failure or rejection is hard. Not getting frustrated with your kid is hard. Breaking the simplest habits is so, so hard.

But it’s the work that counts. It’s the difficulty that remakes you. That asks you to be a deeper, truer version of yourself, in integrity with the world and the people around you. That says to you, you can dream of something greater, and you can make it.

In all honesty, being present with small children is the most difficult thing in our society. Everything begs us to justify our time: today I wrote X number of words and sent X emails and made X dollars!

And time spent playing dolls on the rug in the bedroom is like a muddy river of non-time: endless, excruciating, sometimes incredibly beautiful. But when I sit there and wallow in that time, craving often to be anywhere else – running! Writing! Reading! Cooking! DOING something! – in the end I feel so satisfied.

What I have earned is relationship. Trust. Love. Care. A warmth in the whole house. It is the hardest thing. It is also everything: what we remember on our deathbeds.

Is our homeschool picturesque wooden shelves of tiny felt fairies and adorable bespoke math manipulatives and cherry tarts fresh from the oven? Is our child producing jaw-dropping Harry Potter fan fiction or made-to-scale Lego replicas of the ancient wonders of the world? NOPE!

She is copying out the lyrics to Taylor Swift’s “Karma” because it includes BOTH “hell” and “shit.” She is dressing up in a sparkly leotard and pretending to be a pop star. She is also doing cursive and typing and learning about tardigrades through a Biology curriculum I’m trying out, and she’s about to start folk tales in Spanish. It may work, it may not. Radical risk; failure; start again.

We take Elena back to her old school twice a week so she can finish the Girls On The Run program she started. Bringing her back stirs up intense feelings of grief. For the school itself, the relationships we cherished there, and also for the ease and givenness of relying on that structure.

Accepting that grief is part of the process. I don’t believe choices like these are often neat and tidy and glorious and simplistic, with clear heroes and villains, clear victories and losses. They are wrenching. They are hard. They are profound. They force a radical acceptance of that Buddhist mantra: everything changes. They break us out of the inertia we mostly cling to, even when it is not serving our joy or liberation.

On Elena’s last day at school, a memory popped up on my Facebook feed: it was of Elena surrounded by dolls at a pretend tea party in her bedroom, in fall 2020, and I’d posted “No school” with about twenty sobbing and upside-down-smiley-face emojis. Now, three years later, I was choosing to take her home with me.

We don’t know how long we’ll homeschool. We don’t know what our rhythm will end up being or how hardcore we’ll be about curricula versus self-directed learning versus “unschooling” versus structured classes – we are discovering this world and ourselves anew. This is the trick: leap off the map, draw a new one, learn what you believe a map should even be and feature. That experience in and of itself is an education. What do we want to learn? How? What is worth learning? For me? For our family? For the world? How would you answer these questions for yourself?

What if we bust out that big word: liberation? What does that mean to you, in your context?

To me it means asking the hugest, hardest questions, then asking them again from another angle. It means being willing to question the most fundamental givens in which we’ve all been born and raised: to see the structures around us as choices, not reality.

To be humble about our own limitations and failures and have grace with ourselves that we then extend outwards to the world. To have radical imagination, to be weird and unafraid, to be funny, uncanny, and welcoming of paradox. To put love first in a time of tribal loyalties, insecurities, grief, and fear. To seek joy: for ourselves, for our communities.

It means big dreaming, and attending to and nurturing those dreams in real ways, with awareness and accountability, every day.

I don’t know if we’re up for it.

But we’re gonna try.

I am sure so many of you have thoughts! I would love to hear them. This is such an important topic and I really appreciate a diversity of viewpoints. What has been your experience with school? What are your thoughts on education? Share!

Resources for those of you interested in reading more about homeschooling:

Lauren Markham’s recent Believer piece had a fascinating overview of the national shift towards homeschooling.

What a flock of geese can teach us about consent-based schooling.

School wasn’t so great before COVID, either.

What is self-directed education?

There are so many parts of this essay that I wanted to highlight. Everything you said you really resonated with me; these are all topics I've been thinking about a LOT lately. As someone who has been reading your newsletter since you started it, I'm not surprised about the decision you all have made. I could hear you asking these questions years ago, when the pandemic started and your daughter was out of school. My kids are still very young, so we haven't had to make any formal decisions yet (although I do send my oldest to a small preschool in a church basement), but I have already started stressing. For me, it's the subject of gun violence and lockdown drills that scares me the most, and subsequently the negative affects on kids' mental health. I have a lot of family in Europe and speaking to them about that reality here just really puts it into stark perspective for me; they don't even know what a lockdown drill. Also, there's the fact that my family put a lot of pressure on "getting a good education" and it's definitely a value that I hold. Anyway, thanks for sharing your experience, your thought process, and these resources! I look forward to hearing more about your journey!

well, this sounds like the cliff that you all needed to fall off - and now, I guess, you will find out if the world is, after all, flat! - what sprang into my mind (my kids are in their 20s and went to a quaker secondary school in tasmania) as I was reading this post, is a quote by pema chodron who wrote somewhere that 'the greatest misery is believing something that you know isn't true' - for you, trying to believe in the public school system when, in your bones, you felt increasingly critical of it, was going to have to give - at least this way you have the peace of mind of knowing that you've all had the courage to do what felt like the 'next right thing' (jung), which is perhaps all any of us can do - good luck, helen